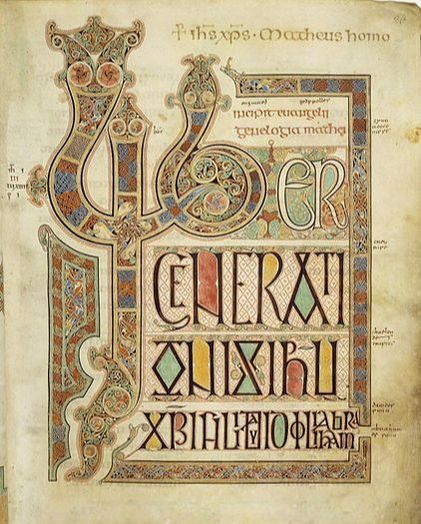

John W. BatemanExecutive Director “Why do they need to say / do that?” “That’s disrespectful!” “I don’t get it…” Art isn’t always about landscapes or pretty patterns that our grandmothers loved. It can provoke, expose new ideas, or challenge old ones. Art is, quite often, inherently political. Some say it’s always political because it either influences or is influenced by society. Has that always been a possibility? Consider centuries-old biblical manuscripts and scrolls. Perhaps the ornate lettering strikes a chord for you. Did you know that, during the 8th and 9th centuries in the Byzantine Empire, bans were briefly imposed on images (referred to as "iconoclasm")? But... the ornate lettering in these manuscripts... aren't they images? Did the monks and scribes who drew these letters (despite the ban) engage in some form of clever political resistance? ("Why are you drawing pictures?! Heretic!" "Aye, that's not a bucket, that's the letter U!") “Why did they need to make those huge letters?” “That color is disrespectful!” “I don’t get it…” We might scoff at that idea of radical monks giggling as they draw images disguised as letters. That is, until we remember stories of church-led persecutions under the much later Spanish Inquisition. Perhaps it isn’t too far fetched, then, to wonder if ornate lettering was an exploration of art and images, right under the very noses of imposing, church-led governments. Fortunately, the First Amendment does a lot more than protect us from a government that tries to impose a specific set of religious beliefs. It allows us to meet in public (freedom of assembly), speak against the government (freedom of speech), publish newspapers and books and blogs (freedom of the press), and file lawsuits (right to petition the government). These underlying rights have always coexisted and, although not without debate or conflict, give room for all of our freedoms to work, particularly when they allow us to challenge those who govern. In other words, the First Amendment is a check and balance against the government itself. Without it, the United States could not exist as we know it today. The First Amendment isn’t about protecting an individual’s personal opinion on whether or not a Thomas Kinkade painting is drivel. It’s David and Goliath: individual liberty versus government control. One goal is fundamental: it protects against government-sanctioned oppression, which, in turn, helps ensure that dissenting voices are heard... even when some folks don't like those voices. It also prevents the government from favoring or funding only those groups (or works of art) that promote the government’s viewpoint. This is precisely why it matters, quite simply, whether a group must be granted a permit for a parade. As Benjamin Franklin wrote in 1737: “Freedom of speech is a principal pillar of a free government; when this support is taken away, the constitution of a free society is dissolved, and tyranny is erected on its ruins.” The freedoms of expression under the First Amendment are integral to the arts. All forms of art (not just print or spoken words) are covered by the First Amendment: plays, music, dance, film, literature, poetry, visual arts (paint, sculpture, ink, photography, etc). Art has tremendous potential for communication, whether through film, newspaper, a tweet or Instagram post, in a library, theatre or museum… and, yes, even within a parade. As a result, government restriction must typically meet the requirements of “strict scrutiny” by demonstrating a compelling state interest in limiting speech (like imposing a fine for yelling “fire” in a crowded theatre). Mere disagreement with content doesn’t meet this high standard, and the exceptions are very limited. That’s a powerful freedom for all of us (and especially artists) to create, communicate, express, and share creative work while having constitutional protection against government censorship, retaliation, or worse. However, even with this protection, the arts are continually challenged. Consider these books, which have been banned (or subjected to attempted bans), here in the U.S. How many surprises do you find?

“Why did they need to write those words?” “That sentence is disrespectful!” “I don’t get it…” Consider these songs, also either banned or subject to attempted censorship. Did you know the Beach Boys is on this list?

“Why did they need to sing those lyrics?” “That song is disrespectful!” “I don’t get it…” If the First Amendment fades, if we fail to maintain its strength, what’s next? Would it be more than a debate over George Carlin’s “Seven Dirty Words”? What if a city once again imposed a Footloose-inspired ban on music? Could another state introduce legislation that outlawed certain photographs taken from public places (fortunately Florida amended that bill)? Could theaters be banned, as they once were in the city of London? The freedoms under the First Amendment rights are individual and collective: they benefit each of us and all of us. If we impede the rights of fellow citizens, then we, in turn, undermine the same rights that protect us... the same rights that protect artists. There can be no “us” or “them” under the First Amendment. Even when we disagree on the content of someone's message, our rights will sink or swim together. Martin Niemollër, a Protestant pastor who spent 7 years in a Nazi concentration camp, said it best with these lines:

If we don’t embrace and protect the freedom of expression, how does that impact the arts? What do we lose next? For further reading, take a look at these resources: Center for Art Law First Amendment Watch Newseum Institute National Coalition Against Censorship |

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

|

P.O Box 2070

Starkville, Mississippi 39760 [email protected] [email protected] 662.268.6231 Hours: Mon - Fri 10am - 2pm ( closed Sat-Sun ) |

|

SAAC is sustained by donors and sponsors. Donations amounts are flexible and can be recurring. Learn more by clicking the button above. |

We need you - whether or not you're an artist! Our biggest 2 events (Art in the Park and Cotton District Arts Festival) require dozens of helping hands, so jump right in! |

©2020 Starkville Area Arts Council. All Rights Reserved.

#starkvillearts #starkvilleartscouncil #starkvilleareaartscouncil

#starkvillearts #starkvilleartscouncil #starkvilleareaartscouncil

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT: SAAC is an equal opportunity organization. We do not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion (creed), gender, gender expression, age, national origin (ancestry), disability, marital status, sexual orientation, or military status, in any of its activities or operations. These activities include, but are not limited to, hiring and firing of staff, selection of volunteers and vendors, operation of programs, and provision of services. We are committed to providing an inclusive and welcoming environment for the public, all members of our staff, volunteers, vendors, and artist communities.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed