Danny ClarkSummer Intern

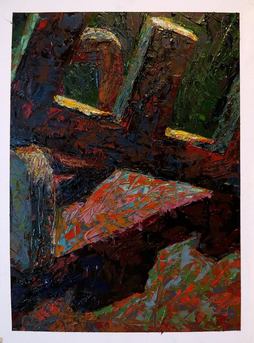

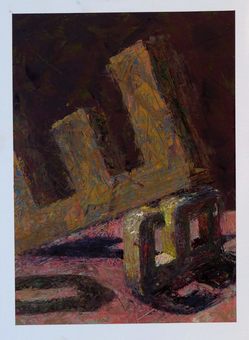

That definition, however, underestimates the power of color as a force. It’s much more than a way to tell the difference between objects. We are moved by color (only one of several elements of art), even when we don’t like it. It’s a bit like gravity: color is embedded with psychology. To see this in action, one only needs to consider the various palettes used in branding. One of the best takeaways from my college experience at Mississippi State University was realizing how little I really understood about seeing, despite an ever-increasing visual society, particularly via social media: instagram, snapchat, twitter, facebook, etc. As a visual artist, it’s important for me to continue my pursuit of an understanding and redefining of color. Kassia St Clair’s The Secret Lives of Color (2017) offers a detailed portrait on a selection of color detailing histories, anecdotes, and psychology. For instance, color can affect the food we choose to eat by making it more aesthetically pleasing. Japanese ceramists use dull earth-toned glazes called Shino’s on tea cups that contrast the vividly saturated matcha green tea. Another example of the psychology of color is on Baker-Miller Pink, which was used to calm hostile conditions in prisons because it lowered heart rates and strength. Did you know that pink, at one point, was considered masculine? In the early 1900’s, boys were dressed in pink because it was a shade of red. Girls, on the other hand, wore blue for its cool qualities and iconic use with the virgin Mary. The word and the color have contextually shifted over time to reflect changes in our culture. For me, as an artist, understanding this psychology offers a temptation (and opportunity) to subvert and question these conventional ideas. Art educator Josef Albers believed that the world is controlled both psychologically and literally by our vision. We become so accustomed to how we “see” things that we take certain ideas for granted. We must fight past all the constructs that suggest meaning behind colors like pink. When Albers talks about visual perception, he means something much more profound than the basic fact of what we see. He describes a magic, something like a deeper reality, that the majority of people miss. Color is NOT an absolute in the way the world suggests (such as masculine or feminine). It lives and moves constantly. I understood this when one of my undergraduate instructors required us to paint white letters and numbers in natural light. None of the assignments looked the same, beyond the measured forms. Each work carried a unique feel, despite the objective nature of the task. Albers states that this “true reality” is available for everyone to see but nobody looks. His describes this “true reality” as a notion to “open eyes,” which is an underserved, largely ironic observation given a culture with so many visual stimuli. Beyond small events, we are rarely given incentive to look beyond the absolute vision that we take for granted. Examples of these small events can be as simple as noticing how light influences what we see. Did you think the dress was black and blue, or white and gold? How does the color of food and the color of the plate our experience with eating? These small events often seem like simple aesthetic questions, but, in reality, they reveal a great deal about our perceptions. These small events are a call to reevaluate how we look at objects and what that reveals about our lives. Color can be appreciated without the forces constructed around it. The world is redefined by my own personal color instead of defaulting to Coca-cola Red or Facebook Blue. It doesn’t take an artist, either! Perhaps, instead of a force, consider color as an event: consider color as a personal experience that is meant to be celebrated. A human phenomenon that only asks us to explore, build, and share. That is the real power of color. |

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

|

P.O Box 2070

Starkville, Mississippi 39760 [email protected] [email protected] 662.268.6231 Hours: Mon - Fri 10am - 2pm ( closed Sat-Sun ) |

|

SAAC is sustained by donors and sponsors. Donations amounts are flexible and can be recurring. Learn more by clicking the button above. |

We need you - whether or not you're an artist! Our biggest 2 events (Art in the Park and Cotton District Arts Festival) require dozens of helping hands, so jump right in! |

©2020 Starkville Area Arts Council. All Rights Reserved.

#starkvillearts #starkvilleartscouncil #starkvilleareaartscouncil

#starkvillearts #starkvilleartscouncil #starkvilleareaartscouncil

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT: SAAC is an equal opportunity organization. We do not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion (creed), gender, gender expression, age, national origin (ancestry), disability, marital status, sexual orientation, or military status, in any of its activities or operations. These activities include, but are not limited to, hiring and firing of staff, selection of volunteers and vendors, operation of programs, and provision of services. We are committed to providing an inclusive and welcoming environment for the public, all members of our staff, volunteers, vendors, and artist communities.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed